Tall in the saddle: Riding out a blizzard with Black Hills ranchers

After losing almost 100,000 cattle to the storm of the century, South Dakota ranchers rebuild with stoic pride.

Originally published in October 2013

I recently returned to my home of six years, the beautiful Black Hills of South Dakota. During my visit, the region was struck by a great and powerful blizzard. The storm was massive and, over the course of four days, dumped almost four feet of snow, cut power to thousands, and killed almost 100,000 cattle on the open range. I wrote about the experience the blizzard and the storm’s ongoing impact on local ranchers.

“My heroes have always been cowboys / And they still are it seems.”

— Willie Nelson

On Wednesday, the sun filtered between tall Ponderosa Pine and orange and yellow quaking Aspen trees, warming Spearfish Canyon. South Dakota’s Black Hills were glowing on the cusp of a colorful fall season.

Then came the snow. And the cold. And the tornados. By Sunday, the Black Hills were digging out from the blizzard of the century, and more than 100,000 dead cattle littered the Western range.

The October 2013 blizzard dropped enough snow to bury fences (as seen in the foreground), partially-submerge cars (background), and tangled yards with power lines.

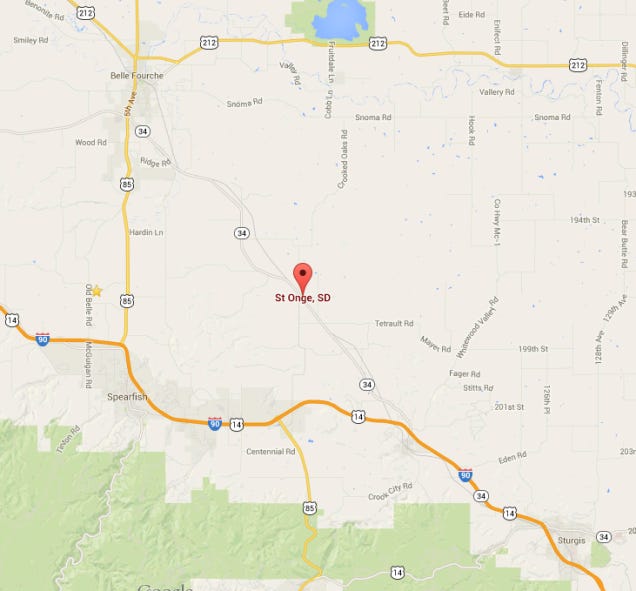

Clint Ridley is a fifth-generation rancher. The Ridley family immigrated from Denmark to Western South Dakota in 1883 and has been working the land ever since. Today Clint tends three ranches and runs Ridley Livestock Company. Ridley’s ranches are near St Onge (map), situated on a beautiful triangle of land about halfway between Belle Fourche and Sturgis, and are sheltered from the great plains by the Black Hills. Cheap but workable land out on the prairie, Ridley told me, can easily be purchased for about $450 an acre. But Ridley’s land, like land owned by many ranchers hit by the blizzard, is worth real money. A savvy buyer with an Eagle-eye on the market is lucky to grab good land close to the Black Hills at a grand acre. And the better the land, the better the cattle.

The blizzard, dubbed Atlas by The Weather Channel and other commercial networks, dropped over 30 inches of snow in the foothills.

The blizzard came suddenly and pounded for two days. First, it rained. Then it snowed. Then the snow piled up, buried cars, and blocked doors. In town, neighbors clung to each other for heat and comfort as thousands of trees — green leaves heavy with fresh, wet snow — bowed and cracked, cutting electricity and heat to thousands almost instantly.

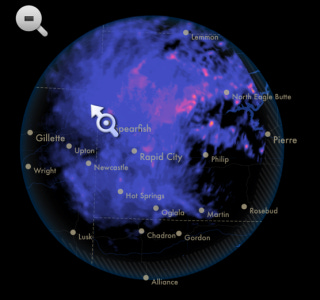

After dropping several feet of snow, Winter Storm Atlas kicked winds up to nearly 70 miles per hour. | Image: The Weather Channel

The blizzard, dubbed Atlas by The Weather Channel and other commercial networks, dropped over 30 inches of snow in the foothills (and reports of up to 7 feet in Deadwood) and dropped the mercury almost 40 degrees in less than 36 hours. The wind gusted up to 68 miles per hour and heaved chest-high banks of snow against buildings. Roads went unplowed and travel by foot or tired-chained truck was nigh-impossible as municipal plow fleets were rendered impotent by the mountain of crushing snow.

Before the wind came, several feet of snow blanketed the Northern Black Hills, paralyzing all traffic. | Photo: Dan Patterson

Anchored by Rapid City, the Black Hills is a mostly rural mountain and high-prairie community of small towns networked primarily by county highways and dirt roads. Like most Westerners, South Dakotans are rawhide-tough and know how to weather a blizzard. But this storm was something different. Atlas was a storm that even the old-timers, cowboys who’ve literally worked the land for generations, had never experienced. According to the Rapid City Journal, Atlas completely buried the old three-day storm record set in 1919.

Typical western storms move from West to East. Atlas moved backward, from East to West, dropped several feet of snow, and spawned tornados. | Image: DarkSkys

Black Hills Power took to Facebook to help residents understand the severity of the storm and prepare for blackouts.

While many towns fought to maintain essential services, mobile social networks played an integral communication role during the storm, as well as with recovery. Interestingly, where electricity failed, cellular and data networks stayed alive (Verizon and AT&T representatives kindly declined to comment on the nature of network infrastructure for this story). With plows buried and trees cracking during and after the storm, Black Hills Power took to Facebook to help residents understand the severity of the storm and prepare for blackouts. While thousands faced the prospect of a week sans power and heat in freezing temperatures, few griped as BHP leveraged social media to manage recovery expectations.

Heather Murschel, a reporter for the Black Hills Pioneer newspaper, was without power or heat for almost a week. While impossible conditions kept her from the newsroom for several days, she used the social web to learn about and disseminate vital information:

To all my fellow neighbors who are without power in Spearfish … just talked to officials at BHP said there are so many secondary lines down that it could days to get power restored to our homes … or it could be tomorrow. They they told me everyone should hope for the best, but prepare for the worst If you haven’t called about a downed power line, call M — in Deadwood at (605) XXX-XXXX [redacted] and she’ll get you on the list. Be nice, she’s had a rough week and being polite and empathetic goes a long way when it comes to the people who determine your “place” on the list. Cheers and stay warm!

Social media became the proverbial dirt road to the local bar during and after the blizzard for rural communities as ranchers used used twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat to stay connected and share stories. As the storm pushed east, many rural dwellers began sharing deeply personal accounts on the web.

Social data application Keepr (string:http://www.keepr.com/index.php?q=bl...) helped track reactions to the Black Hills blizzard in real time. See below for disclosure. | Image: Keepr.com

By Monday, warmer, high-pressure air returned, and the snow began to melt. As friends in town assessed damage and traded shovels and chainsaws, few realized the tragedy emerging from the snow on the high prairie.

South Dakota cattle killed by Atlas. | BigBallsInCowTown.com

One local site, BigBallsInCowTown.com, published a number of striking images (public domain, included in this post) of cattle killed on the range. (Note: the site has been up and down in recent days, here’s a Google cache URL.) What BigBallsInCowTown.com lacks in web technical sophistication, it makes up in authenticity. Images of a few dozen cattle that had dropped dead from exposure hinted at a larger story that would play out quietly across the rural great plains for several months.

The vast prairie of western South Dakota, as seen from the air five days after the blizzard. | Photo: Dan Patterson

Earning a livelihood and raising a family here requires true gumption, an unwavering constitution, and a sober respect for the power of the elements.

Dakota territory is Cowboy Country and stretches from the mighty Missouri in the East to the Big Horns in Wyoming. The Old West was popularized by Laura Ingalls Wilder’s ‘Little House books, made infamous by that dumb bastard Custer, and popularized by Robert Pirsig’s classic escape Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Most people witness the American West from an airplane or car window. But if you’ve experienced the high prairie up close, maybe on a hot summer road trip to Wall Drug and the Badlands, you know how beautiful and intimidating, and expansive the environment can be.

As every rancher will tell you, to make a living from the land is to love the land. Earning a livelihood and raising a family here requires true gumption, an unwavering constitution, and a sober respect for the power of the elements. As with their ancestors, contemporary ranchers still rise early, and tend cattle on horseback (and Ford truck, of course). They often live miles from town down long dirt roads on broken bluffs surrounded by waving grass. Ranching is a lifestyle, and the work is done from the heart, not the wallet.

The Ridley Ranch is perched outside of St Onge, South Dakota. | Image: Google Maps

The Ridley ranch, like many ranches west of Missouri, is a Cow-to-Calf operation. These types of ranches are a cornerstone of the American beef industry and cattle are bred on the range for human consumption. As its name implies, mother cows on Cow-to-Calf ranches birth and raise young calves through the spring, summer, and fall seasons while also pregnant with the next year’s calf. In other words, Atlas hit a crucial and sensitive time in the ranch cycle.

While ranching can pay well, it’s a high-risk, high-cost enterprise. Most ranches operate on a 2–3% margin, and the return on investment — months of long days working the range — usually comes during the auction, only once or twice per year. As a result, most ranchers have little liquid cash and are instead rich in assets like good credit, healthy land, solid houses, strong horses, and big trucks.

Nearly 100,000 cattle dropped dead from the cold, snow, and wind that hammered the range for two days. A healthy cow can fetch close to $2000 at auction. | BigBallsInCowTown.com

Although modern in many ways, ranching remains an industry steeped in tradition, and mother cow and calf are raised with love. “My dad would ride his horse for miles out through the gumbo looking for cows that had given birth,” Ridley told me, referring to the slushy mixture of snow, mud, and grass caused by seasonal wet weather. “He’d somehow get the cow and calf home, and my mother would warm the baby with blankets inside our house.”

October’s storm was devastating. A typical Dakota ranch will carry several hundred head of cattle on about a thousand acres of land. Ranchers across Western South Dakota were preparing to round up this year’s stock for auction, where cattle will usually fetch about $1200 to $1900 per head.

Cattle buckled to the elements en masse, and were pregnant with the next year’s calf. | BigBallsInCowTown.com

“Those old cowboys are too proud to say shit if they had a mouthful of it,” Ridley told me when I naively asked about federal assistance and insurance. Ranching and farming are two very different ventures, and many prideful cowboys scoff at the perceived benefits of farm subsidies. Due to the difficulties in proving losses, most ranchers who could insure their stock don’t bother. According to Ridley, most ranches aren’t insured against storms and are skeptical about insurance companies, “ain’t no insurance adjuster I’ve ever met gonna get on a horse and ride all afternoon looking for the carcass of a dead cow.”

On good land, a rancher can typically park about 250 head of cattle over about 7000 acres. A rough estimate of the damage caused by Atlas could take over a month to assess, though the scale of loss will probably never be truly quantified. Initial reports in the days after the blizzard pegged the loss of cattle at around 40–60 thousand head. But the scale of loss grows with the melting snow, and some ranchers now place the estimated total of lost cattle at close to six figures. Those cattle not lost could lose up to 60 or 70 pounds. And at two bucks per pound at market, the quality loss adds up quickly.

“This past week I’ve seen some of these guys and gals, life-long ranchers tough as nails and just as sharp, sit a bar stool in Belle Fourche and just cry in to their whiskey.

Ranching is a tent-pole industry in the West, and ranchers spend money on everything from local retail shops to big-ticket items like grain, trucks, and houses. Brad Jurgensen, a Rapid City media buyer, and radio personality (better known on-air at local rock station KDDXas ‘Murdoc Jones’), said the regional economic impact of lost cattle could be catastrophic. The week after the storm, some local media outlets predicted that the financial cost of lost cattle could exceed $200 million. That price tag does not include the value of next year’s unborn calf, nor does it include the opportunity cost of a lost season of hard work raising thousands of now-dead mother cows and calves. A quarter-Billion dollar storm would hit any region hard. In South Dakota, an area partially dependent on sensitive industries, no one will escape the economic weight of Atlas.

“In a big storm with wind and snow, [the cattle] can’t see. A lot of ‘em will just get all tangled up in the fence, or stuck down in a creek bed somewhere,”

Land inaccessible by horseback was and will be scouted by air, typically using a low-flying bush plane, the like ’75 Cessna Cub. A few days, or even weeks, on the range is a long time for a large, dead animal to rot. Some ranchers will never know what they really lost, Ridley said.

“In a big storm with wind and snow, [the cattle] can’t see. A lot of ‘em will just get all tangled up in the fence or stuck down in a creek bed somewhere,” Ridley explained, “a month or so later after the snow’s gone, ain’t nothing left to find.” But before the snow is gone, ranchers will be on horseback and in the air, crisscrossing the high prairie counting their losses.

It is easier to appreciate the immense size of the Atlas-affected region from the air. As the brown prairie emerged from melting snow, flying over the Black Hills also revealed small black specs and the unmistakable outline of thousands of dead cattle.

“This past week, I’ve seen some of these guys and gals, life-long ranchers tough as nails and just as sharp, sit on a bar stool in Belle Fourche and just cry into their whiskey. It takes a lot to make some of these old cowboys cry, so that’s saying something,” Ridley said. Ridley is a stoic and sober guy. His voice is strong with just a hint of a cowboy twang. Listening to him talk about the blizzard’s impact on ranchers sounded like a yarn spun from some old Zane Grey novel. But as he explained the culture and business of ranching, Ridley evoked people whose lives are real and who depend on the land for a living.

A week after the blizzard, I spoke with Clint on the phone about recovery. He told me about pitching in down in New Orleans after Katrina. “Look, I don’t want to compare our stuff to theirs, and they went through some stuff,” he said, “but we’ll feel it in a really similar way.”

Looking ahead, the federal government isn’t likely to step in and offer help any time soon. According to The Washington Post, the government shutdown has had a direct impact on Black Hills ranchers. But even if the government was operating, it’s doubtful many ranchers would seek assistance. Instead, South Dakotans rely on each other to pull through hard times.Recovery will be rough, but the West is chock-full of can-do cowboys ready to saddle up for another ride this spring.

“Hell, I gotta go,” Clint said from the Livestock Company, “got some customers.”

Researched & Written By: Dan Patterson October 2013 using Markdown in Byword and Evernote in Spearfish, South Dakota, and Brooklyn, New York.

Edited By: Josh Sternberg.

Thanks To: Hong Qu, Clint Ridley, Murdoc Jones, Chris Cady, and Nick at Killian’s Pub for the heat and bourbon, the Black Hills Pioneer newspaper & Black Hills State University for assistance in fact-checking, those who shared personal stories via Twitter and Facebook, and the good people of the great state of South Dakota.

Disclosure: Research for this article was made possible by an underwriting grant from Keeper.